A group of women gathered to form Busan Art Coalition to Ban Sexual Violence (BSV) to fight against sexual crimes in the creative industry on October 31, 2016.

Since October 2016, a massive #MeToo movement came to rise on social media, revealing the prevalent sexual violence across various industries and regions in South Korea. The #MeToo movement in creative industries particularly shocked many Koreans as the most esteemed artists including Ko Un, Kim Ki-duk, and Cho Jae-hyun were charged with allegations of sexual violence.

Yet a group of artists noticed that Busan, the second largest city in Korea, remained extremely silent during the #MeToo wave, and they knew this did not indicate that Busan had relatively less sexual crimes compared to other cities.

“The silence in Busan meant that it is an environment difficult for sex crime victims to speak out about what happened,” said Cho Eun-ha, an activist at BSV.

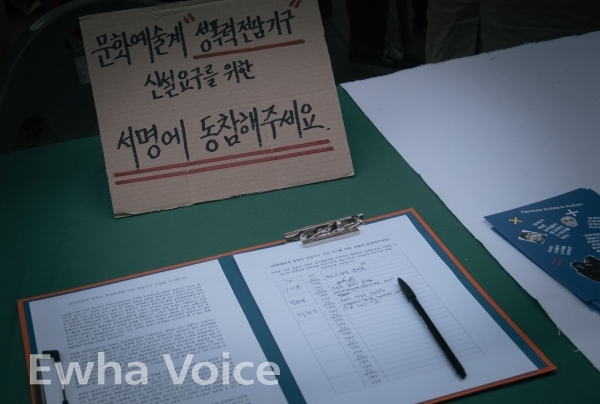

Artists who found the stillness in Busan problematic decided to announce the “Change instead of Silence” statement together with Cho to pledge themselves not to remain silent over sex crimes in creative industries. This led to the formation of an artist-feminist coalition called BSV.

BSV has been holding conferences for victims to speak out, suggesting policies to ban sexual violence in the art industry, and supporting sex crime victims.

According to Cho, victims of sexual crimes in the creative industries face difficulties in making their voices be heard as most of the crimes are committed by teachers, professors, and instructors. She quoted the 2019 statistics from the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism to suggest that 71.3 percent of the sex offenders in the creative industries were older artists, and 50.9 percent of those perpetrators were professors or lecturers.

“Since Busan’s art industry is small and acquainted, the victims have a harder time deciding whether they should report the sexual violence that had happened to them,” Cho said. “The victims fear that the perpetrator’s close professors and senior artists might take away exhibition opportunities and even give disadvantages to their art careers.”

BSV accordingly held press conferences under the victim’s consent or visited the victim’s university president in order to demand stronger measures against the offender to tackle such problems. BSV also composed a code of conduct and provided workshops to emphasize gender equality in creative industries with other art organizations.

But there were difficulties as well. Cho recalled an incident when she was a counselor for sex crime victims several years ago. After BSV found out that a sex offender was teaching minors at a public organization, Cho filed a document to demand an investigation of the offender’s eligibility as a teacher.

The director of the organization, however, broke into BSV’s headquarters without any prior notice. He argued that the teacher at issue is not the type of person who would commit sex crimes, claiming that the teacher has been always very nice to him.

“My perspectives on Korean society shifted drastically after this incident,” Cho said. “I lost my trust in public organizations since they were supposed to fire or dismiss the person if they are a sex offender according to the law.”

Despite such adversities, Cho and other BSV activists are still vigorously combatting sexual violence. Cho expressed that after years of working as an activist to ban sexual violence, she was surprised to see continuous feminist movements in Busan even under its conservative nature.

Cho insisted that the sex crime victims could distance themselves from traumatic memories when the society as a whole demands eradication of sex crimes and sends them huge support. In order to record what the victims had to go through and what BSV activists did in response to such incidents, BSV published a book titled “That is Not Art, it is Sexual Violence” in the hopes that people who did not join the movement could also get a grasp of what happened and would stand with the victims of sexual violence.

“The book was written with blood, sweat, and tears that BSV activists shed on our path to gender equality in the creative industries,” Cho said. “I hope for a world where women’s struggles, voices, and even the most trivial things hold significance.”