“I was all by myself because my husband had bailed on me and my two-year-old son,” Choi said. “I even ate candy that people had dropped on the street because I had been suffering from hunger, and my homeless life continued for two months.”

Choi is now no longer alone, nor is she dressed in rags. Choi may not be rich, but she lives in a rented apartment with her son, enjoying her “home sweet home” moments.

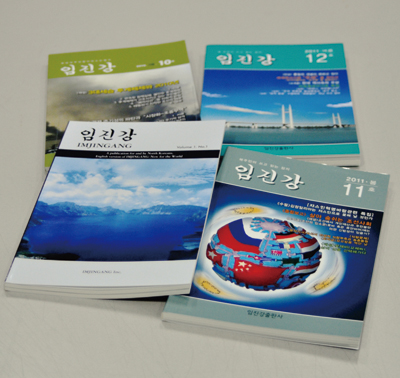

Here in South Korea, Choi is more famous as the chief editor of the quarterly magazine Imjingang than as a female poet. Imjingang is a gateway to learning about North Korea since it consists of articles written by North Koreans and is secretly distributed to North Korean readers through secret hidden channels.

“The title of the magazine was named after ‘Imjingang,’ or Imjin River in Gyeonggi Province,” Choi said. “The Imjin River runs from North Korea to South Korea. I hope our magazine also ‘penetrates’ both Koreas with our astonishing inside news from North Korea.”

Choi was born in Pyeongyang, North Korea in 1959 and was raised by parents who loved literary works. In 1980, Choi submitted two poems to the Pyeongyang Newspaper, which was the very beginning point of Choi’s life as a poet.

“Once, a picky senior poet complimented me, saying, ‘No other female poet is as good as Choi,’” she recalled.

However, Choi and her family had to leave Pyeongyang after three years of marriage, for the North Korean government banished 100,000 people from the city every year due to the country’s food shortage. Choi’s new life as a homeless person, fighting hunger and poverty for two months in Cheongjin, made her decide to cross the Dooman River and go to South Korea. With the help of her cousin, who knew how to cross the border between China and North Korea, she escaped from the North alone.

Later on, Choi recrossed the Dooman River to save her two-year-old son and returned with him to China safely in 1998.

After her arrival in South Korea, she began to search for a new lifestyle, a new education, a new career, and other new things in a new country. Choi decided to study women’s studies, not literature.

“I wanted to study totally something new,” Choi said. “Learning about women’s studies at Ewha, I first learned the concept of ‘sexual violence’ or ‘sexual harassment,’ as there is no expression to distinguish them in North Korea. Many people don’t consider them as crimes.”

To publish Imjingang, Choi stays more than half the year beside a river on the border between North Korea and China. The North Korean reporters of the Imjingang are provided with a laptop and a lesson on news reporting.

“The Imjingang reporters share diverse backgrounds; from teachers to high officials and ordinary citizens in North Korea, they risk their lives to deliver news in North Korea to others,” Choi says.

She pays a lot for the reporters’ risky works, which puts the magazine Imjingang in continuous financial difficulties.

Despite all these hardships and difficulties, Choi hopes and believes that the reunification of Korea is not far away, and she wishes to build a school for smart young North Korean students when the Korean Peninsula is reunified.

“I hope our magazine Imjingang contributes to unification by making North Koreans aware of their rights and helps them learn to improve their lives by themselves,” Choi said.

Yang Su-bin

subinyang@ewhain.net