The winner of the first 2020 EWHA-HYUNWOO Academic Prize was announced on Nov. 10. The prize was established to emphasize and continue Ewha’s history of Women’s Studies, and to award scholars who have greatly contributed to the expansion of knowledge about women in Korea. The first prize recipient is Kim Eun-jung, an associate professor in Women’s and Gender Studies at Syracuse University.

Kim was awarded the prize for highlighting the controversy behind the concepts of “treatment and rehabilitation,” and its relation to national history, disability, gender, and sexuality. Her work was especially well portrayed in her book, “Curative Violence.”

“As an activist participating in the disabled women’s human rights movement, I realized it was crucial to understand how Korean history has shaped the experiences and representations of women with disabilities,” Kim said. “The need to study the relationship between disability, gender, and sexuality in modern Korean history led me to theorize what I call ‘curative violence’.”

In her special lecture following the awards ceremony, she explained that as Korea developed, it focused on curing and rehabilitating the nation and those with disabilities and illnesses. At the same time, this process of curing separated those in the boundary of “normal” from those with certain illnesses, such as Hansen's disease.

First 2020 EWHA-HYUNWOO Academic Prize celebrates studies on women and peace

When forcing “treatment,” segregation, and sterilization, the nation exerted violence against those with certain disabilities and illnesses. Curative violence is also enacted when disability is framed as something that needs to be cured, thereby denying the possibility of living with disabilities.

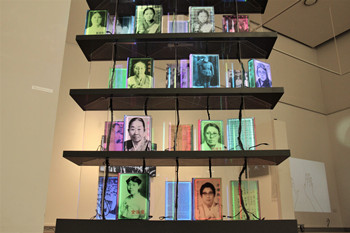

Professor Kang Ai-ran, director of the school’s Korean Women’s Institute, made Kim’s award plaque herself. The plaque was in the form of a writing book, brightly illuminated with LED lights.

“The book contains the meaning that although unopenable, it shines brightly in itself,” Kang said. “It also hints at the significance of the content of the book or research.”

The plaque was in line with Kang’s art piece, which was displayed as rows of books featuring female independence activists, illuminated with LED lights. The piece titled “Women of the Korean independence movement: A hundred years of women’s history opens up a new future,” was displayed at the special exhibition.

The exhibition, “A Larger Mind: Retrieving the nexus of female spaces,” was held from Nov. 9 to 18, to celebrate the first EWHA-HYUNWOO Academic Prize. It aimed to emphasize the impact of internal reflection of female writers, and its relation to a peaceful society.

Kang’s art piece had also been previously displayed at The National Women’s History Exhibition Hall, commemorating the 100th anniversary of the establishment of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea. It honored 33 female independence activists who were less known in comparison to their male counterparts. The purpose of Kang’s art piece was to honor their brilliant achievements and highlight their existence.

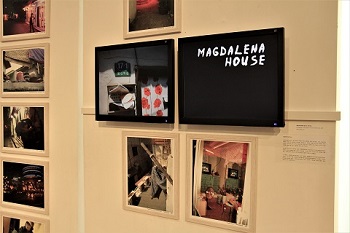

“Our Lives, Our Space: Views of Women in a Red-Light District” was another significant piece in the exhibition. This piece is a combination of pictures taken by workers in the now demolished red-light district in front of Yongsan station. Professor Kim Ae-ryung, of Ewha Institute for the Humanities, explained the motives behind the piece.

Kim stated that the piece was the outcome of an extremely long-term project, initiated by Magdalena Community, which has helped those involved in prostitution since 1985.

“The project started in 2009,” Kim said. “We gave digital cameras to the workers in the Yongsan red-light district to create a comfortable environment for discussion. The participants would share their stories based on the photos they took. It was also a good way to save their memories of the area, since it was due for demolition.”

Through the process, many photos were accumulated, especially photos which broke the stigma that society put upon these workers. They took photos of their daily lives within the district, including animals, flowers, and buildings. The photos caught the interest of American universities, and Magdalena Community was able to have their first photo exhibition in New York University, and Wellesley College. In order to portray the desired meaning and continue the project in Seoul, they created the photo book “Pandora Photo Project.”

Kim emphasized that uncovering formerly hidden aspects of society is what makes the project special.

“The stigma surrounding prostitution nearly erased the whole district from history,” Kim said. “Our photographs and photo book allowed the district to be remembered, not just as a negative place of prostitution, but as a village filled with memories of very brave women.”